Hydrargyrum—what a mouthful! That’s also the other name for quicksilver or mercury, the only metal that is liquid at room temperature (hence hydra + argyrum, or “watery silver”). As a result of this interesting property, mercury has a wide variety of applications. It can be used in thermometers, batteries, dental fillings, and— yes, you guessed it—mining!

Because precious metals are normally found in the ground, the mined ore contains dirt, sand and other non-metallic elements and impurities. The chemical composition of mercury allows it to act as a solvent for metals; in the same manner that salt dissolves in water, mercury can dissolve gold and separate it from the rest of the impurities in the ore.

This mixture is subsequently heated until all the mercury evaporates, as mercury also has a relatively low boiling point. After this, what is left behind is mostly pure gold, that can be further refined with other techniques.

The Amalgamation Process

The process of combining liquid mercury with ores is called amalgamation, whereby the “amalgam” is the mixture created when combining with and dissolving the precious metal.

The amalgamation process provides an efficient way to purify ores and has been used even by the ancient Romans when mining. It can be done even by small-scale miners, for it does not require much heavy machinery relative to other processes.

After extraction, ores are first ground until they are fine enough to allow maximum exposure of the gold to the mercury. The ore can also be mixed with water to help disperse it and promote better adherence of the precious metal, usually gold or silver, with the mercury. Then, in an amalgamation drum or amalgamation table, the fine ore is combined with liquid mercury to combine in a metal-laden amalgam.

The waste material then separates and travels down a chute attached to the amalgamation table or drum.

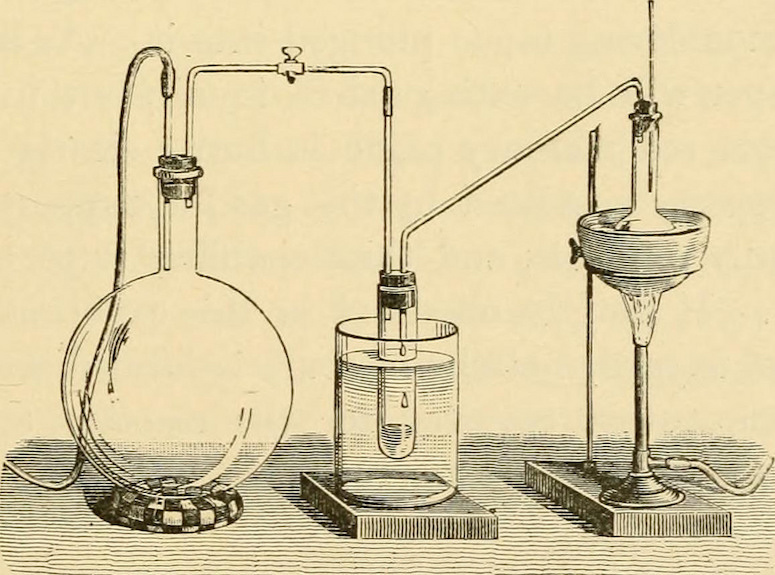

Mercury Retorts

The gold or silver can be recovered from the metal-laden amalgam by a process called “retorting” the mercury. A distillation retort, usually made of cast iron or steel, is a small still used to recover the mercury and leave behind the precious metal.

The amalgam is gradually heated in this retort until the mercury is vaporized and the precious metal is left behind. The vaporized mercury fumes pass through a condenser that recovers the mercury in a separate vessel for potential reuse. The same process can be done on a larger scale using a furnace.

Toxicity and Mercury

This process clearly makes heavy use of mercury. This is problematic simply because mercury is toxic— hence the warnings of not to eat too much fish to avoid mercury poisoning (fish like tuna and swordfish have some concentration of methylmercury, the most toxic form of mercury).

The toxic nature of mercury is also why most common utilizations of mercury have now been replaced; digital and Galinstan-based thermometers are now taking the place of mercury thermometers, lithium batteries have rendered the traditional mercury-zinc batteries quite rare, and ceramic composites are currently used in place of mercury ones in dentistry.

On top of this toxicity, the amalgamation process itself makes the control of mercury quite a challenge. When vaporizing the mercury, some of the fumes may escape and be emitted into the atmosphere. After this, it gets deposited through rain and snow, accumulating in the surrounding bodies of water. The natural ecosystem in these areas then get disturbed. This illustrates the far-reaching consequences of mercury mining, as it has a significant impact that goes well beyond the miners handling it.

Children are some of the most vulnerable to mercury poisoning. In 3rd world countries, children are often involved in mining tasks that expose them to toxic levels of mercury. Often they have no education about the danger associated with using it.

Mercury Use in Mining Now

The decline in mercury mining due to these problems began in the 1960s, but he damage that has been done is quite difficult to reverse. And while the use of mercury in gold mining has reduced substantially in the developed world, the same can’t be said for thousands of small mines around the world.

A website called Mercury Free Mining estimates that there are about 8,000 pounds of mercury being released into the biosphere on a daily basis. Mercury mining and amalgamation is still being done in small-scale or private mines due to its accessibility and efficiency. However, it is important to note that it is still a toxic substance—the risks can be minimized with care, but never fully eradicated.

Gravity Separation Methods Are Recommended

While mercury amalgamation is an efficient process, it’s not the only one out there. One way of accomplishing the same thing is through a variety of gravity separation methods.

The most basic and well known method is panning, which involves separating precious metals from lighter particles in the ore using a curved pan. Water is mixed in with the ore, and as the pan, the heavier gold particles naturally settle at the bottom. The water then carries the other particles away.

Panning works, but it takes skill and a lot of time to separate gold out completely from other minerals. On a large-scale it is not practical.

There is now larger equipment that can separate gold extremely well, removing heavy iron contaminants while leaving just clean gold behind. Gravity shaker tables are the most popular and are very commonly used at larger operations throughout the world. They are expensive, but very efficient when set up properly. And they completely negate the need for mercury in gold mining.

There is now larger equipment that can separate gold extremely well, removing heavy iron contaminants while leaving just clean gold behind. Gravity shaker tables are the most popular and are very commonly used at larger operations throughout the world. They are expensive, but very efficient when set up properly. And they completely negate the need for mercury in gold mining.

Spiral concentrators are a good option for small mining operations. You can purchase them from a mining supplier for a few hundred dollars. Larger styles are available that can handle more volume that will cost thousands of dollars. They can separate out fine gold particles much more efficiently that hand panning.

There are a wide variety of other equipment that use gravity separation to recover gold. Each will have advantages and disadvantages, but the most important thing is that they are non-toxic options.

Mercury has played an important role in gold mining for thousands of years, but it is time to move on. New technologies allow us to capture fine gold without using toxic substances like mercury.

Next: Basic Equipment to Get You Started as a Gold Prospector

Also Read: Crevicing for Gold – Finding Nuggets Deep in the Bedrock