The Alaska Gold Rush actually started with a gold discovery in the Klondike Region of northwestern Canada on August 16, 1896. The remote location and harsh winter prevented widespread reports of the recent gold discovery from reaching Seattle and San Francisco until the summer of 1897.

Like many of the gold rushes before it, excitement ensued, and many men left their jobs and previous lives behind to make the treacherous journey north in the search for gold. Many business men also followed, seeing the great potential making money from the thousands of hopeful miners heading up to the Klondike.

There were several potential routes that the miners could take on their venture north. Each had it’s own unique set of obstacles and difficulties. One of the most appealing routes was by riverboat from the Bering Sea up the Yukon River. This water route seemed like an attractive option, as the miners could avoid difficult land crossings.

This was not as simple as it seemed however, as icy conditions on the river made it extremely difficult for boats to venture far enough up the Yukon River to access the gold bearing Klondike region. Very few of the miners made it this way.

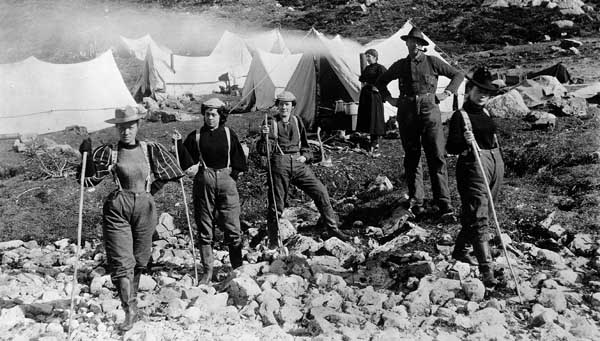

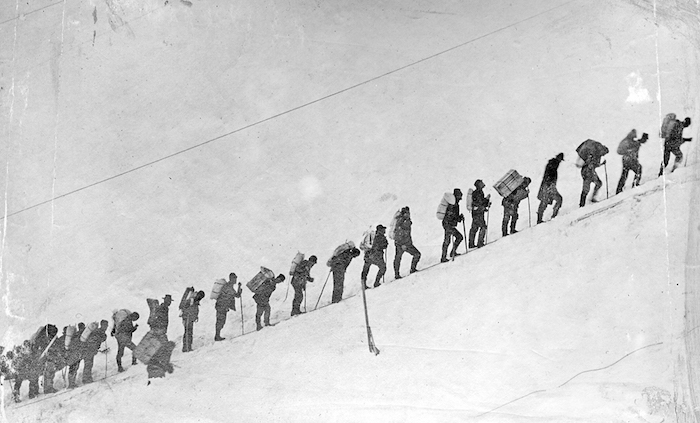

The most commonly used route that the miners took were overland routes from ports in southeast Alaska, taking trails across the Canadian border into the Klondike. The main difficulty was that Canadian authorities regulated the borders and required each man to bring 1 year of food with them, which could weight as much as a ton. Each man would have to take nearly 30 trips back and forth to get the required amount of food and gear across the border.

Horses and other stock were very limited, and what was available was very expensive. Alaskan natives would charge the miners up to $1 per pound to haul gear for them on their backs.

The two overland routes that most men took to the Klondike were from the seaport of either Skagway or Dyea, then over the trails at Whites Pass or Chilkoot. Each had its own unique challenges.

Whites Pass was very treacherous, and many horses died, coining the name “dead horse gulch” at one point along the trail. The sheer volume of men repeatedly crossing the pass eventually made it impassable. More men used Chilkoot Trail, but it was to steep on the back side which prevented the use of stock animals, requiring the men to move all of their supplies on their back, or pulled behind them on a sled.

There was also an overland route to the Klondike through mainland Canada, but it was an extremely difficult journey, and almost no one successfully made it.

After the miners successfully crossed Whites Pass or Chilkoot Pass, they would camp at Lake Bennett and Lake Lindeman near the Yukon River. They built home made boats and drifted down the river to the Klondike. There were no regulations or expertise when it came to building these makeshift boats, and many perished on their journey downstream when they encountered rapids on the Yukon.

Most estimates say that of the 100,000 that started their journey north, only about 30,000 to 40,000 men ever successfully made the journey to the Klondike, and of those only about 4000 struck gold.

As with most gold strikes, most of the good land was claimed up before the masses even arrived, so most were limited to working lower valued claims, or prospecting new areas and trying to get lucky. Only a few hundred men actually got rich, and many of those were the businessmen who sold supplies.

After only a few short years, most of the miners at the Klondike left when news hit that gold had been found at Nome, Alaska, and later in British Columbia at Atlin. Although the Klondike gold strike was actually in Canada, it was the first big gold rush that brought people north searching for gold, and is credited as the start of the Alaskan gold rush.

Next: The Gold Rush to Nome